> To discover order and intelligence in scenes of apparent wildness and confusion is the pleasing task of the geological inquirer. - Dr. Paris.

Of all the monsters that ever lived on the face of the earth, the giant birds were perhaps the most grotesque. An emu or a cassowary of the present day looks sufficiently strange by the side of ordinary birds; but “running birds” much larger than these flourished not so very long ago in New Zealand and Madagascar, and must at one time have inhabited areas now sunk below the ocean waves.

The history of the discovery of these remarkable and truly gigantic birds in New Zealand, and the famous researches of Professor Owen, by which their structures have been made known, must now engage our attention. In the year 1839 Professor Owen exhibited, at a meeting of the Zoological Society, part of a thigh-bone, or femur, 6 inches in length, and 51/2 inches in its smallest circumference, with both extremities broken off. This bone of an unknown struthious bird was placed in his hands for examination, by Mr. Rule, with the statement that it was found in New Zealand, where the natives have a tradition that it belonged to a bird now extinct, to which they give the name Moa. Similar bones, it was said, were found buried on the banks of the rivers. A minute description of this bone was given by the professor, [228] who pointed out the peculiar interest of this discovery on account of the remarkable character of the existing fauna of New Zealand, which still includes one of the most extraordinary birds of the struthious order (“running birds”), viz. the Apteryx, and also because of the close analogy which the event indicated by the present relic offers to the extinction of the Dodo in the island of Mauritius. On the strength of this one fragment he ventured to assert that there once lived in New Zealand a bird as large as the ostrich, and of the same order. This conclusion was more than confirmed by subsequent discoveries, which he anticipated; and, as we shall see, his estimate was a most moderate one, for the extinct bird turned out to be considerably larger than the ostrich. Later on he received from a friend in New Zealand news of the discovery of more bones. In 1843 a collection of bones of large birds was sent to Dr. Buckland, Dean of Westminster, by the Rev. William Williams, a zealous and successful Church missionary, long resident in New Zealand. On sending off his consignment Mr. Williams wrote a letter, of which we give the greater part below.

> Poverty Bay, New Zealand, February 28, 1842. > > Dear Sir, > > It is about three years ago, on paying a visit to this coast—south of the East Cape, that the natives told me of some extraordinary monster, which they said was in existence in an inaccessible cavern on the side of a hill near the river Wairoa; and they showed me at the same time some fragments of bone taken out of the beds of rivers, which they said belonged to this creature, to which they gave the name Moa. > > When I came to reside in this neighbourhood I heard the same story a little enlarged; for it was said that this creature was still existing at the said hill, of which the name is Wakapunake, and that it is guarded by a reptile of the lizard species [genus]; but I could not learn that any of the present generation had seen it. I still considered the whole as an idle fable, but offered [229] a large reward to any one who would catch me either the bird or its protector....

These offers procured the collection of a considerable number of fossil bones, on which Mr. Williams, in his letter, makes the following observations:— > None of these bones have been found on the dry land, but are all of them from the banks and beds of fresh-water rivers, buried only a little distance in the mud.... All the streams are in immediate connection with hills of some altitude. > > 2. This bird was in existence here at no very distant time, though not in the memory of any of the inhabitants; for the bones are found in the beds of the present streams, and do not appear to have been brought into their present situation by the action of any violent rush of waters. > > 3. They existed in considerable numbers”—an observation which has since been abundantly confirmed. > > 4. It may be inferred that this bird was long-lived, and that it was many years before it attained its full size.” This is doubtful. > > 5. The greatest height of the bird was probably not less than fourteen or sixteen feet.” Fourteen is probably the extreme limit. > > Within the last few days I have obtained a piece of information worthy of notice. Happening to speak to an American about these bones, he told me that the bird is still in existence in the neighbourhood of Cloudy Bay, in Cook’s Straits. He said that the natives there had mentioned to an Englishman belonging to a whaling party that there was a bird of extraordinary size to be seen only at night, on the side of a hill near the place, and that he, with a native and a second Englishman, went to the spot; that, after waiting some time, they saw the creature at a little distance, which they describe as being about fourteen or sixteen feet high. One of the men proposed to go nearer and shoot, but his companion was so exceedingly terrified, or perhaps both of [230] them, that they were satisfied with looking at the bird, when, after a little time it took alarm, and strode off up the side of the mountain. > > This incident might not have been worth mentioning, had it not been for the extraordinary agreement in point of size of the bird”—with his deductions from the bones. “Here are the bones which will satisfy you that such a bird has been in existence; and there is said to be the living bird, the supposed size of which, given by an independent witness, precisely agrees.” In spite, however, of several tales of this kind, it is almost certain that these birds are now quite extinct.

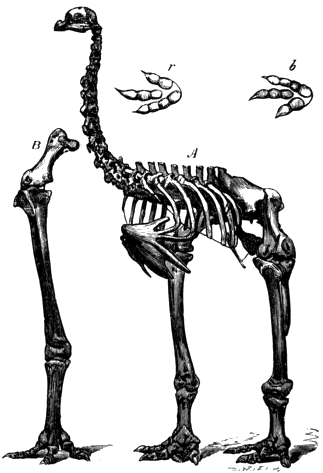

The leg-bones sent to London greatly exceeded in bulk those of the largest horse. The leg-bone of a tall man is about 1 ft. 4 in. in length, and the thigh of O’Brien, the Irish giant, whose skeleton, eight feet high, is mounted in the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, is not quite two feet. But some of the leg-bones (tibiæ) of Moa-birds measure as much as 39 inches. In 1846 and 1847 Mr. Walter Mantell, eldest son of Dr. Mantell, who had resided several years in New Zealand, explored every known locality within his reach in the North Island. He also went into the interior of the country and lived among the natives for the purpose of collecting specimens, and of ascertaining whether any of these gigantic birds were still in existence; resolving, if there appeared to be the least chance of success, to penetrate into the unfrequented regions, and obtain a live Moa. The information gathered from the natives offered no encouragement to follow up the pursuit, but tended to confirm the idea that this race of colossal bipeds was extinct. He succeeded, however, in obtaining a most interesting collection of the bones of Moa-birds, belonging to birds of various species and genera, differing considerably in size. This collection was purchased by the trustees of the British Museum for £200. Another collection was made by Mr. Percy Earle from a submerged swamp, visible [231] only at low water, situated on the south-eastern shore of the Middle Island. This collection also was purchased by the trustees for the sum of £130. Mr. Walter Mantell, who described this locality, near Waikouaiti, seventeen miles north of Otago, thinks it was originally a swamp or morass, in which the New Zealand flax once grew luxuriantly. The appearance and position of the bones are similar to those of the quadrupeds embedded in peat-bogs, as, for instance, the great Irish elk (see next chapter). They have acquired a rich umber colour, and their texture is firm and tough. They still contain a large proportion of animal matter. Unfortunately, even when Mr. Walter Mantell visited this spot, the bed containing the bones was rapidly diminishing from the inroads of the sea, and perhaps by this time is entirely washed away. Mr. W. Mantell, however, obtained fine specimens and feet of a large Moa-bird (Dinornis) in an upright position; and there seems to be little doubt that the unfortunate bird was mired in the swamp, and perished on the spot. The bones which he obtained from the North Island presented a different appearance, being light and porous, and of a delicate fawn-colour. They were embedded in loose volcanic sand. Though perfect, they were as soft and plastic as putty, and required most careful handling. They were dug out with great care, and exposed to the air and sun to dry before they could be packed up and removed. The natives were a great source of trouble to him, for as soon as they caught sight of his operations they came down in swarms—men, women, and children, trampling on the bones he had laid out to dry, and seizing on every morsel they could get. The reason of this was that their cupidity and avarice had been excited by the large rewards given by Europeans in search of these treasures. Mixed with the bones he found fragments of shells, and sometimes portions of the windpipe, or trachea. One portion of an egg which he found was large enough to [232] enable him to calculate the size of the egg when complete. “As a rough guess, I may say that a common hat would have served as an egg-cup for it: what a loss for the breakfast-table! And if many native traditions are worthy of credit, the ladies have cause to mourn the extinction of the Moa: the long feathers of its crest were by their remote ancestors prized above all other ornaments; those of the White Crane, which now bear the highest value, were mere pigeon’s feathers in comparison.” The total number of species of Moa once inhabiting New Zealand was probably at least fifteen, and, judging from the enormous accumulations of their bones found in some districts, they must have been extremely common, and probably went about in flocks. “Birds of a feather flock together” (proverb). It is justly concluded, both from the vast number of bones discovered, and from the fact of their great diversity in size and other features, that they must have had the country pretty much to themselves; or, in other words, they enjoyed immunity from the attacks of carnivorous quadrupeds. In whatever way the Moas originated in New Zealand, it is evident that the land was a favourable one, for they multiplied enormously, and spread from one end to the other. Not only was the number of individuals very large, but they belonged (according to Mr. F.W. Hutton) to no less than seven genera, containing twenty-five different species, a remarkable fact which is unparalleled in any other part of the world. The species described by Professor Owen in his great work,[75] vary in size from 3 ft. to 12 or even 14 ft. in height, and differ greatly in their forms, some being tall and slender, and probably swift-footed like the ostrich, whilst others were short and had stout limbs, such as Dinornis elephantopus (Fig. 56), which was undoubtedly a bird of great strength, but very heavy-footed. Dinornis crassus also had stout limbs. (See Plate XXIII.)

- Memoir on The Extinct Wingless Birds of New Zealand. London, 1878. The beautiful drawing by Mr. Smit (Plate XXIV.) is from a photograph in this valuable work representing the late Sir Richard Owen standing in his academic robes by the side of a specimen of the skeleton of the great Dinornis maximus.

PlateXXIII.

MOA-BIRDS.

Dinornis giganteus. D. elephantopus.

Height 12 feet. A smaller species. - source ![]()

The Natural History Museum at South Kensington contains a valuable collection of remains of Moa-birds. These skeletons may be seen in Gallery No. 2 (at the end of the long gallery) in the glass cases R, R´, and S. Dinornis elephantopus (elephant-footed) is in front of the window.

Fig. 56.—A. Skeleton of the Elephant-footed Moa, Dinornis elephantopus, from New Zealand. B. Leg-bones of Dinornis giganteus, representing a bird over 12 ft. high.

r, b, footprints. - source ![]()

In D. giganteus the leg-bone (see Fig. 56) attains the enormous length of 3 ft., and in an allied [234] species it is even 39 in.! The next bone below (cannon bone) is sometimes more than half the length of the leg-bone (tibia).

A skeleton in one of the glass cases has a height of about 101/2 ft., and it is concluded that the largest birds did not stand less than 12 ft., and possibly were 14 ft. high!

Dinornis parvus (the dwarf Moa) was only three feet high.

In 1882 the trustees obtained, from a cave in Otago, the head, neck, two legs, and feet of a Moa (D. didinus), having the skin, still preserved in a dried state, covering the bones, and some few feathers of a reddish hue still attached to the leg (Table case 12). The rings of the windpipe may be seen in situ, the sclerotic plates of the eye, and the sheaths of the claws. One foot also shows the hind claw still attached. From traditions and other circumstances it is supposed that the present natives of New Zealand came there not more than about six hundred years ago, and there is reason to believe that the ancient Maoris, when they landed, feasted on Moa-birds as long as any remained. Their extermination probably only dates back to about the period at which the islands were thrice visited by Captain Cook, 1769-1778. The Moa-bird is mixed up with their songs and stories, and they even have a tradition of caravans being attacked by them. Still, some people believe that they were killed off by the race which inhabited New Zealand before the Maoris came. But they must have been there up to a time not far removed from the present. It is even said that the “runs” made by them were visible on the sides of the hills up to a few years ago; and possibly they may still be visible. The charred bones and egg-shells have been found mixed with charcoal where the native ovens were formerly made, and their eggs are said to have been found in Maori graves. Mr. Hutton considers that in the North Island they were exterminated three or four centuries ago, while in the South Island they may have lingered a century longer. The nearest ally of the Moa is the small Apteryx, or Kiwi, of [235] New Zealand, specimens of which may be seen at the Natural History Museum, at the end of the long gallery devoted to living birds. This bird, however, has a long pointed bill for probing in the soft mud for worms, whereas the bill of the Moa was short like that of an ostrich. Another difference between the two is that, while the Kiwi still retains the rudiments of wing-bones, the Moa had hardly a vestige of such. In Australia the remains have been found of a bird probably related to the Cassowaries, but at present imperfectly known. To this type of struthious, or running bird, the name Dromornis has been given. Now, it is a remarkable fact that remains of another giant bird and its eggs have been found on the opposite side of the great Indian Ocean, namely, in the island of Madagascar, the existence of which was first revealed by its eggs, found sunk in the swamps, but of which some imperfect bones were afterwards discovered. One of these eggs was so enormous that its diameter was nearly fourteen inches, and was reckoned to be as big as three ostrich eggs, or 148 hen’s eggs! This means a cubic content of more than two gallons! The natives search for the eggs by probing in the soft mud of the swamps with long iron rods. A large and perfect specimen of an egg of this bird, such as was recently exhibited at a meeting of the Zoological Society, is said to be worth £50. What the dimensions of Æpyornis were it is impossible to say, and it would be unsafe to venture a calculation from the size of the egg.[76] The reader who wishes to see some of the remains of this huge bird may be referred to the Natural History Museum. In wall case No. 25, Gallery 2 (Geological Department), may be seen a tibia and plaster casts of other bones; also two entire eggs, many broken pieces, and one [236] plaster cast of an egg found in certain surface deposits in Madagascar. In the same case may be seen bones of the Dodo from the isle of Mauritius. Unlike New Zealand, Madagascar possesses no living wingless bird. But in the neighbouring island of Mauritius the Dodo has been exterminated less than three centuries ago. The little island of Rodriguez, in the same geographical province, has also lost its wingless Solitaire.

[76] From the size of a femur and tibia of Æpyornis preserved in the Paris Museum, it could not have been less in stature than the Dinornis elephantopus of New Zealand. It will thus be seen that we have three distinct groups of giant land birds—the Moas, the Dromornis, and the Æpyornis,—occupying areas at present widely separated by the ocean. This raises the difficult but very interesting question, how they got there; and the same applies to their living ancestors. The ostrich proper, Struthio camelus, inhabits Africa and Arabia; but there is evidence from history to show that it formerly existed in Beluchistan and Central Asia. And, going still further back, the geological record informs us that, in the Pliocene period, they inhabited what is now Northern India. In Australia we have the Cassowary (Casuarius) and the Emeu (Dromaius); in New Zealand, the Apteryx (or Kiwi). Now, as none of these birds can either fly or swim, it is impossible that they could have reached these regions separated as they now are; and it is hardly likely that they arose spontaneously in each district from totally different ancestors. But the new doctrine of evolution affords a key to the problem, and tells us that they all sprang from a common ancestor, of the struthious type (probably inhabiting the great northern continental area), and gradually migrated south along land areas now submerged. In this way we get some idea of the vast changes that have taken place in the geography of the world during later geological periods. Perhaps they were compelled to move south until they reached abodes free from carnivorous enemies. Having done so, they evidently flourished abundantly, especially in New Zealand, where there are so few mammals, except those recently introduced by man.

[237]

In North America Professor Cope has reported a large wingless fossil bird from the Eocene strata of New Mexico. In England we have two such—namely, the Dasornis, from the London Clay of Sheppey (Eocene period), and the Gastornis, from the Woolwich beds near Croydon, and from Paris (also Eocene). It will thus be seen that big struthious birds have a long history, going far back into the Tertiary era, and that they once had a much wider geographical range than they have now. Doubtless, future discoveries will tend to fill up the gaps between all these various types, both living and extinct, and to connect them together in one chain of evolution. The last great find of Moa-birds in New Zealand took place only last year, and was reported by a correspondent to the Scotsman (November 13, 1891), writing from Oamaru. In the letter that appeared at the above date, our friend Mr. H. O. Forbes announces the discovery of an immense number of bones, estimated to represent at least five hundred Moas! They were found in the neighbourhood of Oamaru. And, after some preliminary remarks, he continues as follows:— > The part of the field on which the remains were found bears no traces of any physical disturbance—e.g. of earthquake, or flood, or hurricane—that would account for the sudden destruction of a flock or ‘mob’ of Moas. The Moa, when alive, carried in its crop—like our own hens—a quantity of stones to serve as a private coffee-mill for digestive grinding; stones which, being somewhat in proportion to the magnitude of the giant bird, form, when found in one place, a ‘heap’ of stones which are easily identified as a Moa heap, and nothing else. And in the present case the heap was here and there found in such relation to the bones of an individual bird as to show that the Moa must have died on that spot, and remained there quietly undisturbed. Further, the number of birds represented by the exhumed remains is so great that the living birds could not have stood together on the space of ground on which the remains were found lying. And [238] there is not on any of the bones any trace of such violence as must have left its mark if the death of the birds had been caused by a Moa-hunting mankind. Finally, it does not appear that in this particular district there ever has been, at any traceable period of the physical history of the land, a forest vegetation, such as might suggest that the catastrophe was caused by fire. > > The question how to account for the slaughter is raised likewise by two previous finds of Moa bones. The first of these, at Glenmark, in Canterbury, was the most memorable, because, being the first, it made the deepest impression. The second great find, far inland, up the Molineux River, otherwise the Clutha, was beneath the diluvium that is now worked by the gold-digger. The spot must have been the site of a lagoon, at one point of which there was a spring. Round about this point there were found the remains of, it was reckoned, five hundred individual Moas. The bones were quietly laid there, with, in some cases, the ‘heap’ of digestive stones in situ along with the skeletons. And Mr. Booth, whose elaborate investigation of this case is recorded in the annual volume of The New Zealand Institute, suggested the theory that the climate of New Zealand was changing to a degree of cold intolerable to Moa nature; and that the birds, fleeing from its rigour, sought comfort in the spring of water, sheltering their featherless breast in it, and so dozing out of this troubled life. And in this new find the wonder comes back unmitigated, as a mystery unsolved. For here is no bog deep enough, as in the first instance, nor lagoon spring, as in the second, to account for that multitude of giant birds dying in one spot. > > Another curious puzzle is, on close inspection, found everywhere in the Moa bone discoveries. It is hardly possible to make sure that the bones of any one complete Moa skeleton all belong to the same individual I heard some one say the other day that it is not certain that any Moa in any earthly museum has all his own bones, and only his own.

[239]

> A main interest of such a find lies not in the power of supplying museums with specimens of what is rapidly disappearing from the face of the world, but in the possibility of finding species of Moa that have not hitherto been tabulated. Whether any new species have been brought to light on this occasion the experts will not say until there has been time to make a careful study of the bones, nor do they venture on any theory to account for there being so many individual birds dead in that one place, where there appears to be no room for the explanations offered in connection with previous great finds. The date of these birds appears to be earlier than that of the coming of the Maoris into New Zealand, say five or six hundred years ago, as the Maori memory appears to have in it no trace of feasting on these giant Moas, but celebrates the rat-hunt in its ancient heroic song. And your readers may picture their appearance by noticing the fact that one of the recently found bones must have belonged to a Moa fourteen feet high!

Note.—For further information on this interesting subject, the reader is referred to a paper in Natural Science, October, 1892, by Mr. F. W. Hutton. In a valuable paper, read before the Royal Geographical Society by Mr. H. O. Forbes, March 13, 1893, the lecturer alluded to the important fact that bone belonging to big extinct struthious birds have been discovered in Patagonia. This is interesting news as bearing upon the theory of a former Antarctic continent connecting Australia and New Zealand with South Africa, and perhaps even with South America. After the lecture, to which we listened with great interest, the subject was discussed by Mr. Slater, Dr. Günther, and Dr. Henry Woodward. For ourselves we can see no great difficulty in accepting the theory that such a continent once existed, though it is out of harmony with the now rather fashionable theory of “the permanence of ocean basins”—a doctrine which seems to have been pressed too far.