This is an example page regarding the research on a historical character where some of the material is in the public domain and much is not.

Born John Henry Holliday, August 14, 1851 Griffin, Georgia, U.S. Died November 8, 1887 (aged 36), Glenwood Springs, Colorado, U.S. Resting place Pioneer Cemetery (a.k.a. Linwood Cemetery), Glenwood Springs, Colorado, U.S.

> Note: to find material on “Doc Holliday” in the public domain, the best approach is to follow the paper trail rather than the legend. Holliday appears most clearly when institutions collide with violence: arrest sheets, preliminary hearings, sworn testimony, extradition paperwork, and newspapers trying to sound certain about uncertain events. Those materials tend to be older than the mythology, and many of them are free of copyright restriction because of their age, their government origin, or both.

Initial Research

Doc Holliday (John Henry Holliday) moves through the historical record like a man half-made of paper and half-made of smoke. He was born in Georgia in 1851, trained as a dentist, and then—after tuberculosis began to shape the limits of his future—drifted into the frontier economies of gambling rooms, saloons, and reputations. The story the West tells about him is a story about a dying man who refuses to be reduced to “patient”, and instead becomes a companion, a liability, a sharp-tongued witness, and sometimes a weapon.

Doc Holliday's graduation photo in March 1872 from the Pennsylvania School of Dentistry - wikipedia ![]()

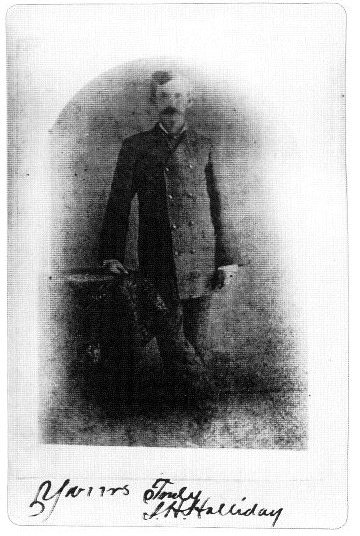

Autographed portrait, Prescott, Arizona, c. 1879 - wikipedia ![]()

# The court-room Doc The most famous body of Holliday-related court material is the aftermath of the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (October 26, 1881). Four days later, Ike Clanton filed murder charges, and Justice of the Peace Wells Spicer convened a preliminary hearing to decide whether the Earps and Holliday should be bound over for trial. This hearing generated extensive testimony, including statements by Wyatt Earp and many other witnesses. For public-domain purposes, the crucial distinction is between the 1881 testimony itself (old enough to be public domain) and later edited publications or modern transcriptions (which may add a new layer of copyright in selection, annotation, or formatting). A useful example is the UMKC Law “Famous Trials” site: it is an excellent reading copy, but it explicitly cites a 1992 edited source for at least some pages, which means the presentation you are viewing can involve modern copyright even when the underlying words are from 1881. If you want a “clean” public-domain presentation, Wikisource hosts the hearing testimony in a format intended to be freely reusable, and it anchors the material to the 1881 proceeding itself. That makes it one of the simplest starting points for public-domain-friendly reuse and remix.

# The extradition and the long tail of Tombstone Holliday’s legal shadow did not end with Spicer’s decision. In 1882 he was arrested in Denver on an Arizona warrant related to the killing of Frank Stilwell, and extradition politics became part of the story. Even when you are reading a modern narrative about this episode, it points you toward the kinds of primary sources that are often public domain in practice: gubernatorial correspondence, arrest notices, and newspaper coverage. The same is true of the “vendetta” aftermath and the shifting status of the Earp faction as they moved across jurisdictions. For public domain research, the practical move is to look for contemporary newspaper scans and government documents, then treat later retellings as maps to those originals rather than as the originals themselves.

# Leadville: the last courtroom Holliday’s last major violent episode with a solid documentary footprint took place in Leadville, Colorado, when he shot William “Billy” Allen after threats and a confrontation tied to a small debt. Accounts agree on the broad arc: Allen was wounded, Holliday was charged, and a jury eventually acquitted him. A commonly cited acquittal date in secondary summaries is March 28, 1885, after a trial late in March. This matters for public domain work because it gives you a date-and-place target for hunting original newspaper reporting (Leadville papers, Denver papers, telegraphed briefs), and for locating court docket references in local archives. Even when the full court file is not digitised, the newspaper coverage often is, and newspapers from the 1880s are typically usable in the public domain (subject to jurisdiction and scan-provider terms).

# Photos and images There are relatively few widely accepted authentic photos of Holliday, and provenance arguments are part of the landscape. Even Wikipedia’s overview of Holliday’s photographs stresses that many “Doc” images circulate without reliable provenance, and that serious researchers want a documented chain of custody rather than a facial comparison. In practice, the most reuse-friendly image sources are public-domain libraries and aggregators that are explicit about rights status. A good example is PICRYL, which aggregates public domain and “no known restrictions” media from major collections and makes it easier to search across them. If you use Wikimedia Commons, pay attention to the licensing notes on each specific file. Commons often hosts a “public domain in the United States” image while warning that the status may differ elsewhere, which matters if you are publishing globally.

# What is safely in the public domain In the United States, most material you will want for Holliday is public domain because it is (a) a 19th-century publication like a newspaper, (b) a government record, or (c) a photograph published long before the modern copyright cutoff. The practical result is that you can often build a richly sourced Holliday page using only primary materials: 1881 hearing testimony, 1880s newspaper accounts, and period photographs whose publication dates are clear. But “public domain” is not the same as “free of all strings”. Scans, transcriptions, and edited compilations can introduce new rights claims even when the underlying work is old. So when you find a beautiful PDF, a nicely modernised transcript, or a curated “best of” document collection, treat it as a pointer to the originals, not automatically as the original itself.

# A field guide to finding the good stuff Start with the O.K. Corral preliminary hearing, because it is both famous and text-heavy, and it pins Holliday to dates, locations, and named witnesses in a way that legend cannot. Use Wikisource when you want a public-domain-first presentation, and use UMKC or Famous Trials when you want convenient navigation and commentary, while remembering that convenience layers may be copyrighted. Then pivot to newspapers around three clusters of dates: late October to November 1881 (Tombstone), May to June 1882 (Denver extradition episode), and August 1884 to March 1885 (Leadville shooting and trial). You are not just hunting stories; you are hunting names of courts, judges, charges, and hearing dates, because those are the hooks that let you request or locate archival files later. Finally, for imagery, prefer collections that declare public domain or “no known restrictions”, and keep a high bar for provenance. Holliday is a magnet for miscaptioned photographs, and the internet will happily hand you “Doc” portraits that are really just “Victorian man with moustache”.

# Sources

- Wyatt Earp hearing testimony - en.wikisource.org ![]() - Wyatt Earp testimony - law2.umkc.edu

- Wyatt Earp testimony - law2.umkc.edu ![]() - famous-trials.com

- famous-trials.com ![]() - Doc Holliday - wikipedia

- Doc Holliday - wikipedia ![]() - picryl.com

- picryl.com ![]() - commons.wikimedia.org

- commons.wikimedia.org ![]() - historynet.com

- historynet.com ![]() - truewestmagazine.com

- truewestmagazine.com ![]()

# See - Gunfight at the O.K. Corral - Wells Spicer - Wyatt Earp - Big Nose Kate - Public Domain

# Images Here are some examples of images of uncertain provenance:

Image from freeinfosociety.com. They don't say where they got it - freeinfosociety.com ![]()

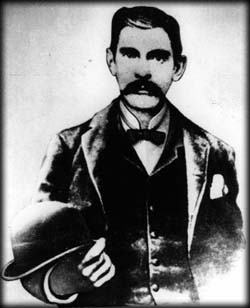

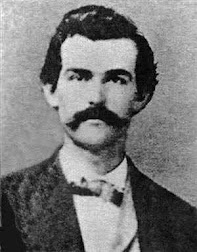

Doc Holliday of unknown provenance - lens ![]()

Doc Holliday. There is controversy regarding this photo - wikipedia ![]()

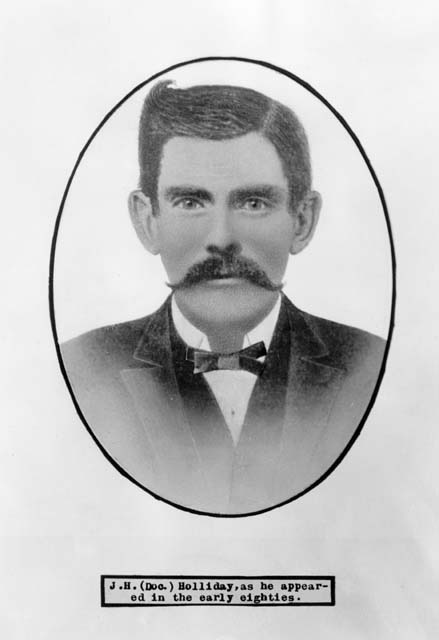

Doc Holliday. Often shown creased, and with light eyes, when not toned. Has unsymmetric detachble upturned shirt collar, with left collar wing pointed more toward camera - wikipedia ![]()