> “And some rin up the hill and down dale, knapping the chucky stanes to pieces wi' hammers like sae many road-makers run daft. They say ’tis to see how the warld was made.”—St. Ronan’s Well.

Our first group of monsters is taken from a tribe of armed warriors that lived in the seas of a very ancient period in the world’s history. Like the crabs and lobsters inhabiting the coasts of Britain, they possessed a coat of armour, and jointed bodies, supplied with limbs for crawling, swimming, or seizing their prey. They were giants in their day, far eclipsing in size any of their relations that have lived on to the present time. Some of them, such as the Pterygotus (Fig. 1, p. 26), attained a length of nearly six feet. They belonged to the humbler ranks of life, and, if now living, would without doubt be assigned, by fishmongers ignorant of natural history, to that vague category of “shell-fish” in which they include crabs, lobsters, mussels, etc. These lobster-like creatures, though claiming no relationship with the higher ranks of animals, may well engage our attention, not only for their great size, but also for their strange build.

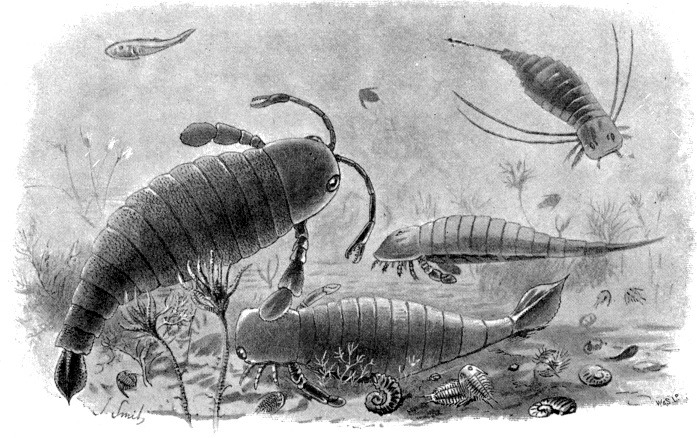

Plate I. SEA-SCORPIONS. Pterygotus anglicus. Length 6 feet. Eurypterus. Stylonurus.

- source ![]()

There are no living creatures quite like them. Certainly they are not true lobsters, and yet we may consider them to be first or second cousins of those ten-footed crustaceans[4] of the present day—lobsters, crabs, and shrimps, so welcome on the tables of both rich and poor. Some naturalists say that their nearest relations at the present day are the king-crabs inhabiting the China seas and the east coast of North America; and there certainly are some points of resemblance between them. Others say that they are related to scorpions, and for this reason we call them Sea-scorpions. (See Plate I..)

[4] Crustaceans are a class of jointed creatures (articulate animals), possessing a hard shell or crust (Lat. crusta), which they cast periodically. They all breathe by gills.

The first feature we notice in these creatures is the way in which their bodies and limbs are divided into rings or joints. This fact tells us that they belong to that great division of animals called “Articulates,” of which crabs, lobsters, spiders, centipedes, and insects are examples. The celebrated Linnæus called them all insects, because their bodies are in this way cut into divisions.[5] But this arrangement has since been abandoned. However, they are all built upon this simple plan, their bodies being like a series of rings, to which are attached paired appendages or limbs, also composed of rings, some longer and some shorter. Now, there must be something very fitting and appropriate in this arrangement, for the creatures that are thus built up are far more numerous than any other group of animals. They must be particularly well qualified to fight the battle of life; for like a victorious army they have taken the world by storm, and still remain in possession. We find them everywhere—in seas, rivers, and lakes; in fields and forests; in the soil, and in all sorts of nooks and crannies; in the air, and even upon or inside the bodies of other animals. Some of them, such as ants, bees, and wasps, show an intelligence that is simply marvellous, and have acquired social habits which excite our admiration.

[5] Lat. in, into, and secta, cut.

Articulate animals are a very ancient race, as well as a flourishing one, for the oldest rocks containing undoubted fossils—namely, certain slates found in Wales and the Lake District—tell us of a time when shallow seas swarmed with little articulate animals known as trilobites. They were in appearance something like [26] wood-lice of the present day; and the record of the rocks tells us plainly that creatures built upon this plan have flourished ever since. We mention this because they are related to the king-crabs of the present day, and therefore to the huge old-fashioned sea-scorpions we are now considering.

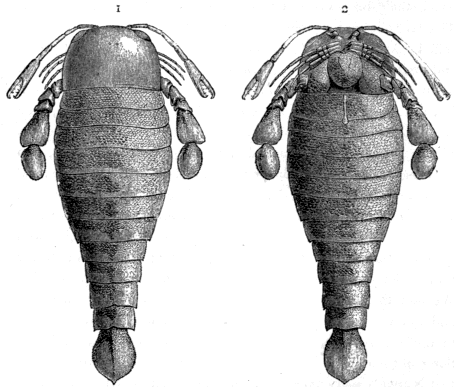

Fig. 1. Pterygotus anglicus. 1. Upper side. 2. Under side - source ![]()

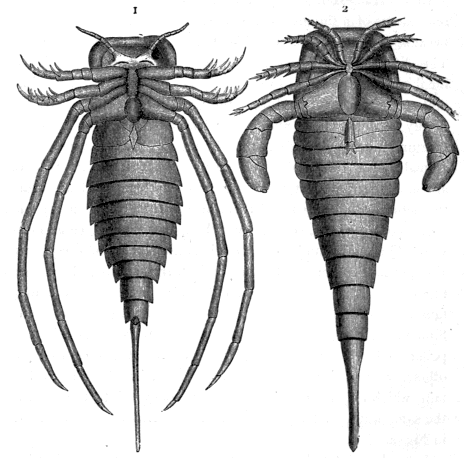

The best-known and largest of these creatures is represented in Fig. 1. It has received the name Pterygotus (or wing-eared) from certain fanciful resemblances pointed out by the quarrymen. It was first discovered, along with others of its kind, by Hugh Miller, at Carmylie in Forfarshire, in a certain part of the Old Red Sandstone (see Table of Strata, Appendix I.) known as the Arbroath paving-stone. The quarrymen, in the course of their work, came upon and dug out large pieces of the fossilised remains [27] of this creature. Its hard coat of jointed armour bore on its surface curious wavy markings that suggested to their minds the sculptured feathers on the wings of cherubs—of all subjects of the chisel the most common. Hence they christened these remains “Seraphim.” They did not succeed in getting complete specimens that could be pieced together; and the part to which this fanciful name was given turned out to be part of the under side below the mouth. It was composed of several large plates, two of which are not unlike the wings of a cherub in shape. Hugh Miller says in his classic work, The Old Red Sandstone—“the form altogether, from its wing-like appearance, its feathery markings, and its angular points, will suggest to the reader the origin of the name given it by Forfarshire workmen.” A correct restoration, in proportion to the fragments found in the Lower Old Red Sandstone, would give a creature measuring nearly six feet in length, and more than a foot across. Pterygotus anglicus may therefore be justly considered a monster crustacean. The illustrious Cuvier, who, in the eighteenth century founded the science of comparative anatomy (see p. 5), astonished the scientific world by his bold interpretations of fossil bones. From a few broken fragments of bone he could restore the skeleton of an entire animal, and determine its habits and mode of living. When other wise men were unable to read the writing of Nature on the walls of her museum—in the shape of fossil bones—he came forward, like a second Daniel, to interpret the signs, and so instructed us how to restore the world’s lost creations. Hugh Miller submitted the fragments found at Balruddery to the celebrated naturalist Agassiz, a pupil of Cuvier, who had written a famous work on fossil fishes; and he says that he was much struck with the skill displayed by him in piecing together the fragments of the huge Pterygotus. "Agassiz glanced over the collection. One specimen especially caught his attention—an elegantly symmetrical one. His eye brightened as he contemplated it. ‘I will tell you,’ he said, turning to the company—'I [28] will tell you what these are—the remains of a huge lobster.' He arranged the specimens in the group before him with as much ease as I have seen a young girl arranging the pieces of ivory in an Indian puzzle. There is a homage due to supereminent genius, which Nature spontaneously pays when there are no low feelings of jealousy or envy to interfere with her operations; and the reader may well believe that it was willingly rendered on this occasion to the genius of Agassiz." Agassiz himself, previous to this, had considered such fragments as he had seen to be the remains of fishes. As we have said before, this creature was not a true lobster; but Agassiz, when he expressed the opinion just quoted, was not far off the mark, and did great service in showing it to be a crustacean. There were no lobsters or scorpions at that early period of the world’s history, and this creature, with its long “jaw-feet” and powerful tail, was a near approach to a king-crab on the one hand and scorpion on the other. If living now, it would no doubt command a high price at Billingsgate; but, then, it would be a dangerous thing to handle when alive, and might be more troublesome to catch than our crabs or lobsters. The front part of its body was entirely enveloped in a kind of shield, called a carapace, bearing near the centre minute eyes, which probably were useless, and at the corners two large compound eyes, made up of numerous little lenses, such as we see in the eye of a dragon-fly. This is clearly proved by certain well-preserved specimens. There are five pairs of appendages, all attached under or near the head. Behind the head follow thirteen rings, or segments, the last of which forms the tail, two at least of these bore gills for breathing. All but two of them, below the mouth, must have been beautifully articulated, so as to allow them to move freely, as we see in the lobster of the present day. But look at that lowest and largest pair of appendages, the end joints of which are flattened out, and you will see that they must have been a powerful oar-like apparatus for swimming [29] forwards. We can fancy this creature propelling itself much in the same way as a “water-beetle” rows itself through the water in a pond. In all other crustaceans the antennæ are used for feeling about, but in the Pterygotus they are used as claws for seizing the prey. In general external appearance, this huge Pterygotus greatly reminds us of a tiny fresh-water crustacean, known as Cyclops—because it has only one eye, like the giant in Homer’s Odyssey. This little creature, which is only 1/16 inch in length, is an inhabitant of ponds. From its large eyes, powerful oar-like limbs, or appendages, and from the general form of its body, Dr. Henry Woodward (the author of a learned monograph on these creatures) concludes that the Pterygotus was a very active animal; and the reader will easily gather from its pair of antennæ, converted at their extremities into nippers, and from the nature of its “jaw-feet,” that the creature was a hungry and predaceous monster, seizing everything eatable that came in its way. The whole family to which it belongs—including Pterygotus, Eurypterus, Slimonia, Stylonurus, and others—seems to have been fitted for rather rapid motion, if we may judge from the long tapering and well-articulated body. In two forms (Pterygotus and Slimonia) the tail-flap probably served both as a powerful propeller, and as a rudder for directing the creature’s course; but others, such as Eurypterus and Stylonurus, had long sword-like tails, which may have assisted them to burrow into the sand, in the same way that king-crabs do. Eurypterus remipes is shown in Fig. 2. It has been stated above that our sea-scorpions are related to the king-crabs. Now, this creature, it is well known, burrows into the mud and sand at the bottom of the sea. This it does by shoving its broad sharp-edged head-shield downwards, working rapidly at the same time with its hinder feet, or appendages, and by pushing with the long spike that forms a kind of tail. It will thus sink deeper and deeper until nothing can be seen of its [30] body, and only the eyes peep out of the mud. It will crawl and wander about by night, but remains hidden by day. Some of them are of large size, and occasionally measure two feet in length. They possess six pairs of well-formed feet, the joints of which, near the body, are armed with teeth and spines, and serve the purpose of jaws, being used to masticate the food and force it into the mouth, which is situated between them.

Fig. 2.—Silurian merostomata.

1. Stylonurus. 2. Eurypterus.

(After Woodward.) - source ![]()

Now, this fact is of great importance; for it helps us to understand the use of the four pairs of “jaw-feet” in our Sea-scorpions. [31] What curious animals they must have been, using the same limbs for walking, holding their prey, and eating! Look at the broad plates at the base of the oar-like limbs, or appendages, with their tooth-like edges. These are the plates found by Hugh Miller’s quarrymen, and compared by them to the wings of seraphim. You will easily perceive that by a backward and forward movement, they would perform the office of teeth and jaws, while the long antennæ with their nippers—helped by the other and smaller appendages—held the unfortunate victim in a relentless grasp. And even these smaller limbs, you will see from the figure, had their first joints, near the mouth, provided with toothed edges like a saw. With regard to the habits of Sea-scorpions, it would not be altogether safe to conclude that, because in so many ways they resembled king-crabs, they therefore had the same habit of burrowing into the soft muddy or sandy bed of the sea, as some authorities have supposed. Seeing that there is a difference of opinion on this subject, the author consulted Dr. Woodward on the question, and he said he thought it unlikely, seeing that, in some of them, such as the Pterygotus, the eyes are placed on the margin of the head-shield; for it would hardly care to rub its eyes with sand. Whether it chose at times to bury its long body in the sand by a process of wriggling backwards, as certain modern crustaceans do, we may consider to be an open question. If only Sea-scorpions had not unfortunately died out, how interesting it would be to watch them alive, and to see exactly what use they would make of their long bodies, tail-flaps, and tail-spikes! Were they nocturnal in their habits, wandering about by night, and taking their rest by day? Such questions, we fear, can never be answered. But their large eyes would have been able to collect a great deal of light when the moon and stars feebly illumined the shallower waters of the seas of Old Red Sandstone times; and so there is nothing to contradict the idea. Now, it is an interesting fact that young crabs, soon after they [32] are hatched, have long bodies somewhat similar to those of our Sea-scorpions, with a head-shield under which are their jaw-feet, and then a number of free body-rings without any appendages. These end in a spiked tail. As the crab grows older, he ceases to be a free-swimming animal—for which kind of life his long body is well suited,—tucks up his long tail, and takes to crawling instead. Thus his body is rendered more compact and handy for the life he is going to lead. Lobsters, on the other hand, can swim gently forwards, or dart rapidly backwards. Thus we see that the ten-footed crustaceans of the present day are divided into two groups—the long-tailed and free-swimming forms, such as lobsters, shrimps, and cray-fishes; and the short-tailed crawling forms, namely, the crabs. Now, in the same way, Pterygotus and its allies were long-tailed forms, while the king-crabs are short-tailed forms. So were the trilobites of old. Hence we learn that, ages and ages ago, before the days of crabs and lobsters, there were long-tailed and short-tailed forms of crustaceans, just as there are now, only they did not possess true walking legs. They belonged to quite a different order, called “thigh-mouthed” crustaceans, Merostomata, because their legs are all placed near the mouth; and, as we have already learned, were used for feeding as well as for purposes of locomotion. Now, one of the many points of interest in Pterygotus and its allies is that they somewhat resemble the crab in its young or larval state. To a modern naturalist, this fact is important as showing that crustacean forms of life have advanced since the days of the sea-scorpions. Their resemblance to land-scorpions is so close that, if it were not for the important fact that scorpions breathe air instead of water, and for this purpose are provided with air-tubes (or trachea) such as all insects have, they would certainly be removed bodily out of the crustacean class, and put into that in which scorpions and spiders are placed, viz. the Arachnida. But, in spite of this important difference, there are some naturalists in [33] favour of such a change. It will thus be seen that our name Sea-scorpions is quite permissible. Hugh Miller described some curious little round bodies found with the remains of the Pterygotus, which it was thought were the eggs of these creatures! Finally, these extinct crustaceans flourished in those ages of the world’s history known as the Silurian and the Old Red Sandstone periods. As far as we know, they did not survive beyond the succeeding period, known as the Carboniferous.[6] [6] The student should consult Dr. Henry Woodward’s valuable Monograph of the British Merostomata (Palæontographical Society), to which the writer is much indebted. With regard to the representation of Pterygotus anglicus in Plate I.., it has been pointed out by Dr. Woodward that the creature was unable to bend its body into such a position as is shown there. As in a modern lobster, or shrimp, there were certain overlapping plates in the rings, or segments, of the body, which prevented movement from side to side, and only allowed of a vertical movement.